The Miami Circle

6/11/2025

The Miami Circle was uncovered in 1998 during the excavation for a luxury condominium at Brickell Point in Downtown Miami. The developer demolished an existing apartment complex that year but only hired archaeologists for a field survey after pressure from the Miami-Dade Historic Preservation Division Director. The survey, conducted by municipal employees, volunteers, and the Archaeological & Historical Conservancy, designated the 2.2-acre site as Miami Midden No. 2.

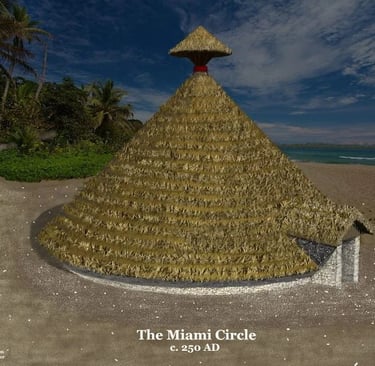

What began as a brief survey led to discovering an ancient rectangular hole cut into the Oolitic limestone bedrock, about two feet deep. Following the director's order for further exploration, more holes revealed a distinct pattern. A surveyor noted a circular pattern 38 feet in diameter by calculating the center of the discovered holes, using CADD to predict locations of additional holes. Excavation uncovered 24 holes forming a perfect circle.

This structure is believed to have been constructed between 0 AD and 300 AD, based on radiocarbon dating of decomposed wood found in some limestone holes. Critics argue that older wood may have accumulated in the slots, suggesting the Miami Circle could be younger.

When the 38-foot diameter circle at Brickell Point and its radiocarbon date became public, claims emerged it was “an Olmec or Maya city.” Some archaeologists argued there were no permanent settlements north of Mexico at that time, suggesting the Miami Circle represented the oldest known permanent habitation in North America. This is inaccurate; Poverty Point in northern Louisiana dates to around 1,600 BC, and by 0 AD, several permanent agricultural villages existed in northern and central Georgia.

Inside and outside the main structure, there are hundreds of smaller holes. Artifacts from a maritime hunter-gatherer culture, similar to that of the Tekesta Indians from southeast Florida, were found above the stone foundation, except for three stone axes made from basalt, an igneous stone not found in Florida.

Dr. Jacqueline Dixon of the University of Miami reported that the basalt likely came from the Macon, Georgia area, about 600 miles away. While basalt is absent around Macon, deposits exist farther north near Atlanta. Basalt, which fractures easily, is not ideal for making axes and wedges. Dixon noted the similarity of these axes to those found at Ocmulgee National Monument in Macon, but those axes were made of greenstone from Dahlonega, GA, 140 miles north of Macon in the Georgia Mountains. This area supplied greenstone tools to Native peoples across eastern North America pre-Europe.

Since its discovery, the Miami Circle has stirred controversy in both archaeology and Miami politics. Florida anthropologists agree that the structure was built by the Tequesta Indians, based on the presence of fishing artifacts near the circle. However, such tools are common across the Caribbean and northern South America.

In 2012, geologists found that a massive comet or asteroid struck the Atlantic Ocean in 539 AD, causing a tsunami larger than those in Sumatra (2005) and Japan (2011). The tsunami initially swept Biscayne Bay's shores clean before depositing other artifacts.

The developer initially planned to remove the section of rock with holes and relocate it for condominium construction, backed by Miami’s mayor. Two local governments were involved: the City of Miami and Miami-Dade County. The county employed the Historic Preservation Commission, while the city handled building plan reviews.

Public opposition increased, with an alliance of preservationists, architects, archaeologists, Native Americans, and students protesting the removal, fearing it could destroy a significant archaeological find. This assertion gained national media attention. The Elizabeth Ordway Dunn Foundation donated $25,000 for further exploration, continuing until February 1999.

In late January 1999, the City of Miami issued permits for Brickell Point. On January 31, 1999, the Dade Heritage Trust filed a lawsuit against the city, seeking an injunction to halt construction. The Trust’s pro bono attorney arranged an emergency hearing with Circuit Court Judge Thomas Wilson.

The Heritage Trust’s lawsuit claimed the developer lacked necessary approval from the City’s Historic and Environmental Preservation Board. Essentially, the city failed to comply with Florida and U.S. laws. At Judge Wilson’s hearing, both the developer and the City were represented by counsel, placing the Historic Preservation Division in a difficult position against municipal and county government. The Heritage Trust’s attorney conceded they weren’t ready to post a bond for the injunction.

Judge Wilson denied the temporary injunction, misinterpreting the National Historic Preservation Act and Florida laws, which don’t require citizens to post bonds against government violations. Still, the developer agreed to delay construction for thirty days for archaeological work.

The Miami Circle controversy led to varying interpretations of its significance. Some articles label it as “the oldest permanent village” on the Eastern Coast, while websites claim it as the 3,000-year-old capital of an ancient Tequesta civilization or a 6,000-year-old stone temple. Others suggest it was a temple built by Atlantis survivors, with artists depicting it as resembling Greek temples or extraterrestrial spaceports.

Despite differing opinions from archaeologists, architects, and the public about the Miami Circle's age and purpose, it is clear that indigenous peoples in northern South America built round communal structures long before they appeared in southeastern North America. Additionally, Arawaks in Cuba and other Caribbean islands constructed similar round buildings, suggesting that they or other South Americans inhabited Cuba when the Miami Circle was built—possibly making Miami the first stop in their journey to North America.

The developer agreed to a 30-day construction delay at the hearing. An alliance involving the County Mayor of Miami-Dade and historic preservationists requested that the Miami-Dade County Commission sue for ownership of the property. The Commission approved this on February 18, resulting in a temporary injunction against the City of Miami and the developer, which prohibited any construction.

The developer initially requested $50 million but later agreed to sell the property to the county for $26.7 million, realizing the county could pursue eminent domain legal action. He profited $18.2 million minus pre-development costs. In a historic move, the State of Florida's Preservation 2000 Land Acquisition Program purchased the site from the developer for that amount in November 1999, utilizing state matching funds and private donations.

On February 5, 2002, the Miami Circle was added to the National Register of Historic Places. History Miami, previously the Historical Museum of Southern Florida, signed a 44-year lease for the site in March 2008 and currently offers tours. It became a National Historic Landmark on January 16, 2009, and a waterfront park managed by History Miami opened in 2011. The Miami Circle remains buried for protection, but an audio tour and panels are available.

Artifacts from the Miami Circle are stored and displayed at History Miami Museum, the official repository for archaeological materials from Miami-Dade County. On February 3, 2014, the Miami Herald reported additional postholes excavated in Downtown Miami, providing evidence of a significant indigenous community. The new site has multiple house sites marked by postholes dating to around 600 AD.

The lack of media attention on the Miami Circle underscores issues with Native American archaeological sites in southern Florida. Large sites around Lake Okeechobee and the Caloosahatchee River receive little care; only one is listed on the National Register and none are state or federally owned historic parks. Politics play a role, as northern Florida sites near Tallahassee get more publicity and protection than those in South Florida.

The state and citizens of Florida spent $26.7 million to acquire Brickell Point property, with at least $2 million more on consultants, legal fees, and landscaping. This was to protect a 38-foot diameter circle of pits in limestone, along with several hundred postholes. Much of the narrative around the Miami Circle is speculative—its surroundings need thorough study before speculation can become fact.

Meanwhile, significant archaeological zones in South Florida are being neglected or developed. A solution should have been adopted to preserve the Miami Circle's surroundings while allowing for some development, countering the developer's demand for a $20 million profit before construction.